THE MENA AI OPPORTUNITY: CREATING VALUE AT THE APPLICATION LAYER

INTRODUCTION: DEFINING THE AI ECOSYSTEM

MENA, and particularly the GCC, stands at a pivotal moment in the global AI race. As detailed in our AI Agent report, the ecosystem can be viewed as a three-layer inverse pyramid: infrastructure at the base, models in the middle, and applications at the top. This structure not only reflects the technical progression from hardware to end-user value but also the concentration of players: very few at the infrastructure layer, more at the model layer, and the most at the application layer. As we have previously outlined, the greatest opportunity lies in the application layer, a view reinforced by recent global developments.

The infrastructure layer includes data centers and compute resources, which require significant capital and are dominated by global and regional giants. While it can offer attractive returns when demand is high, long-term returns are generally aligned with its lower risk profile, and opportunities for new entrants are limited.

The model layer has seen a surge of investment, with tech giants and startups pouring billions into developing ever-more powerful LLMs and AI engines. Yet the landscape is increasingly crowded and leadership can shift rapidly, as seen with DeepSeek’s disruption at a fraction of the cost. Globally, the race to build advanced general-purpose models is as much about national security and strategic autonomy as it is about technology. As such, as open-source alternatives proliferate and geopolitical tensions rise, the risk-reward profile for investing in general models is becoming less attractive.

ZOOMING IN ON THE APPLICATION OPPORTUNITY

In contrast, the application layer is becoming increasingly compelling. Falling API costs, improving model performance, and the ability to tailor AI solutions to local needs, languages, and regulations lower the barrier to building transformative applications. This enables both startups and established companies to rapidly prototype, scale, and refine AI-powered products for specific markets and use cases.

In the GCC, immediate equity value at the application layer is estimated at over $18 billion, with $23 billion in potential savings for companies, a figure expected to multiply as AI adoption accelerates and models improve. This is especially true in Saudi Arabia, where rapid digital transformation, ambitious national initiatives, and a young, tech-savvy population create fertile ground for AI-powered products and services.

Despite the impressive speed of AI adoption in the GCC, driven by government initiatives, cross-sector collaborations, and a robust startup pipeline, we are still in the early days. Most deployments are in chatbots, virtual assistants, and basic automation, while the full potential in sectors like healthcare, logistics, and energy is just beginning to be realized. Investments in Arabic NLP, cloud computing, and data infrastructure are laying the groundwork for more sophisticated, locally relevant applications.

The global AI landscape is evolving rapidly, and the dynamics of competition are far from settled. While market capitalization and adoption are growing at an unprecedented rate, R&D spend on AI remains in its early stages.

THE CASE FOR A GCC-GROWN GLOBAL AI GIANT

Some fear the GCC will be dominated by global AI giants, but local champions have emerged in SaaS and digital platforms by leveraging regulatory insight, deep local integration, and understanding of regional needs. The regulatory environment, data sovereignty requirements, and local integration create natural barriers to entry for international competitors. For instance, local fintechs like Tabby have outperformed global players by aligning with local regulations and consumer preferences, while platforms like Salla and Zid thrive by offering features tailored to the Saudi market.

Our thesis is clear: The GCC is uniquely positioned to create leading AI applications and specialized models, distinct from the general-purpose LLMs dominating headlines. Four enablers are critical: capital, talent, data, and governance. While capital and talent are being addressed, including through our AI fund, the true differentiators will be data and governance. For example, Saudi Arabia’s vast, often sovereign, data assets, held by family businesses and public institutions, provide a foundation for specialized, high-impact AI solutions. Much of this data cannot leave the country, making it a strategic asset for developing models tailored to local challenges. By incentivizing enterprises to “platformize” proprietary data and establishing robust governance, the GCC can catalyze the development of effective and compliant specialized models and applications.

The window of opportunity is wide open, but the pace of change is relentless. Those who act boldly at the application layer will define the future of AI in the GCC and beyond.

AI AGENTS: A REGIONAL OPPORTUNITY WITH GLOBAL POTENTIAL

INTRODUCTION

Gen AI has the potential to reshape the entire service industry, with value creation opportunities estimated in the trillions. Just as the SaaS revolution gave rise to numerous billion-dollar companies, the Gen AI revolution could achieve similar, if not greater, outcomes.

The GCC has both the right to play and the right to win. Now is the time for swift action, taking bold, effective steps to seed local players that can become tomorrow's global champions and multi-billion-dollar success stories.

Every ambitious journey starts with a pragmatic approach. This report focuses on Gen AI (not broader AI), and the immediate and low-hanging fruit opportunities for Saudi Arabia and the GCC. We foresee the potential for around ten GCC-based Gen AI companies worth $1-3 billion each within the next five years. These estimates consider Gen AI applications to deliver at least $23b of cost efficiencies within the GCC while excluding the greater upside from revenue enhancement solutions and geographical expansion.

1. AI Agents: a booming global opportunity

This time it’s different

When assessing AI's potential today, we should not rely too heavily on historical trends and past impacts in the fields. Historically, AI capabilities were restricted to forecasting and classification. With Generative AI, machines are now capable of content generation and reasoning, which unlocks new opportunities that were previously out of reach.

Content generation involves an AI model autonomously creating new material (e.g., text, images, and audio) based on its training data, producing unique content similar to human work.

Generative AI basic reasoning works by recognizing patterns in data and using them to make decisions, rather than relying on strict logical rules like conventional AI systems. This allows it to learn from unstructured data and handle uncertainty. These abilities open up a wide range of new possibilities for AI applications.

As investors, we believe the majority of value to be captured in the Generative AI value chain lies in the application layer; i.e. those who are consuming the models to solve specific business use cases. We prefer the application layer over the model layer because: i) it requires a lower capital investment, ii) it involves less regulatory and copyright risk, and iii) there are no significant training costs. For example, a recent Stanford study reported that training OpenAI’s GPT-4 cost $78 million, while Google Gemini’s training cost $191 million. On the other hand, a prototype for a generative AI application can be developed with a few thousands of dollars.

The best way to understand the “Application Layer” opportunity is to compare it to the SaaS boom. The visual below presents a simplified view of the SaaS value chain (left) alongside the Gen AI value chain (right). On the SaaS side, while "Infrastructure" and "Platform" players capture great value, they require significant capital to gain market share and have been mainly commoditized. Similarly, on the Gen AI side, we believe that the "Infrastructure" and "Platform" layers offer less attractive risk-reward returns. Instead, the application layer, particularly AI Agents, will benefit most from the groundwork laid by infrastructure and platform providers.

Application-layer Gen AI is exciting as it gives birth to a new paradigm of human-computer interaction: AI Agents. We believe the base case for AI Agents is to have a role in most industries and to augment (and, in rare cases, replace) many job functions. This change will be rolled out and normalized steadily in the coming years.

Sites, Apps, Agents

The web gave us Sites, smartphones gave us Apps, and Gen AI will provide us with Agents.

As a new paradigm, a vast ecosystem is being built around the development, monitoring, security, and scaling of AI Agents.

What is an AI Agent? It is intelligent software that understands and interprets natural language, reasons and makes decisions based on input, interacts with users in a human-like manner, and takes autonomous actions (including using multiple apps like a human would) to accomplish a task.

Classical AI attempted to mimic agent-like systems using chatbots and if-then rules. The limits of these approaches were easy to discover. On the other hand, LLM-based agents are perceived and behave in manners that resemble humans.

VC Focus and Emerging Use Cases

Historically, investing in "AI Agents" was not a prominent theme for VC funding. However, as the opportunity in the application layer of AI has become more evident, VCs have started to gravitate towards the investment theme of "agentic startups," those developing AI Agents or creating tools and components to build, monitor, secure, enhance, or scale AI Agents.

The US has seen a significant influx of fresh capital into AI agent startups. Excluding OpenAI, over $1 billion has been invested in solutions built on existing foundational models, with a 64% CAGR over the last two years, which is remarkable considering that overall VC investment dropped by 47% during the same period.

VC Deployment in GenAI

A similar trend is evident in emerging markets like India, where total VC funding declined by 75%, yet AI investment surged with an 87% CAGR over the same timeframe.

This trend is also observed in accelerators. Y Combinator’s latest cohort (Summer 2024), Silicon Valley’s most sought-after accelerator, saw 255 accepted applications. Out of those, 76% were directly or indirectly AI Agent startups. For comparison, Summer 2021 had 18% that were directly or indirectly AI Agent startups.

YC batches breakdown by cohort, (S: summer, W: winter)

Theoretically, AI Agents could augment or replace the entire service industry, a $16 trillion global market. Today, however, there are a few functions that represent low-hanging fruit for current technology to tackle:

The four categories above are undoubtedly incomplete. For example, one of the most exciting use cases for AI Agents has been Software Engineering augmentation and automated code generation (e.g., Cursor, an AI-enabled code editor raised $60mn in 2024). Other categories include a plethora of developer-facing tools and platforms to enable the orchestration and scaling of AI Agents.

How does this impact the bottom line? Each of those companies have a long list of case studies on how they helped their clients by reducing costs or increasing revenue. A recent example of employing generative AI in the workforce is Klarna, the FinTech giant of Europe. Earlier this year, the company launched an AI assistant powered by OpenAI’s infrastructure. According to their press release, the assistant:

Produced the work equivalent of 700 full-time agents

Saved ~20% in customer service and operation costs

Achieved ~25% drop in repeat inquiries

Achieved ~80% improvement in resolution time

All while maintaining same customer satisfaction score

In the next sections, we quantify the potential economic impact on GCC public and private companies.

2. There is massive potential for KSA and GCC

There is an immediate opportunity to create AI agent companies worth $18b in aggregate by serving the GCC market only. Such value creation could materialize in 10 companies, each reaching an equity valuation of $1-3 bn by focusing on a specific use case.

An indicative estimate of the potential equity value of AI agents’ companies

In comparison, the technology ventures that have emerged as successful in the GCC so far had a combined value at exit of less than $10bn. Additionally, given the nascency of the AI Agent field, such winners could easily grow beyond our region.

While the calculation methods used here can be challenged and argued, the exercise is meant to develop a sense of the magnitude of the opportunity.

AI agents: $23bn in saving potential for GCC companies

AI agents could generate savings of $4bn for Tadawul (excluding Saudi Aramco), $13bn for Saudi companies, and $27bn for GCC companies.

The above estimates are based on generative AI technology available today and do not factor in potential future innovation.

Methodology to estimate potential savings from agentic solutions

The split of potential savings by sector is a function of the sector's size and the relevance of AI agents within each sector.

For each sector, we identified the relevant use cases for AI agents and the related corporate functions impacted by them (e.g., customer service, marketing, etc.).

We then selected the major industry players listed in Tadawul and applied the cost-saving ratio to the cost base of the impacted function. Finally, we inferred savings to the broader sector through the relative market share of analyzed players.

We estimate that AI agents can enable 10%-30% savings on average of the impacted functions and 4%-8% savings in the overall operating cost for most sectors, with meaningful value creation potential for shareholders. Some industries benefit from them more than others, depending on their relative reliance on impacted functions and profitability level.

AI agent: a booster for tech ventures

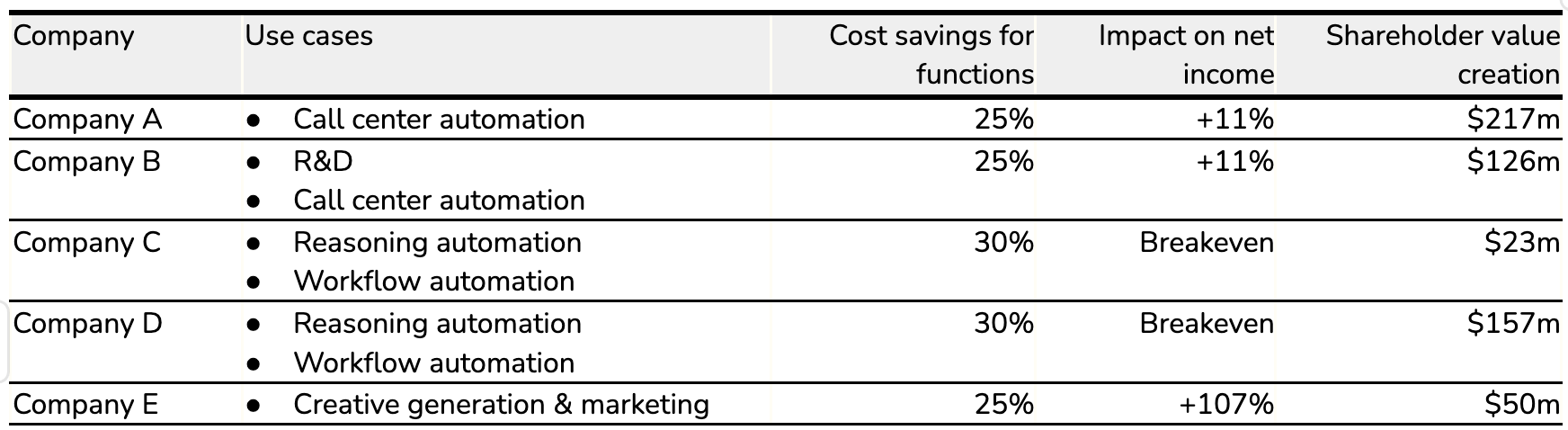

The impact of AI agents adoption on GCC digital ventures is even more significant compared to traditional established businesses in light of the higher weight of their operating costs relative to their revenue. In the exercise below, we selected five STV portfolio companies and analyzed their potential cost savings when using agentic solutions. Given the company valuation and the impact of such a transition on the bottom line, we translated that saving to potential shareholder value.

Cost savings potential for select STV portfolio companies

Looking again at select companies from the STV portfolio, we believe the impact of AI agents on revenue generation outweighs the cost benefits.

Revenue generation potential, examples for select STV portfolio companies

Like many, we believe the near future will bring unicorns with incredibly lean cost structures, some even run by a single person, particularly in specific sectors and business models.

In summary, cost savings and revenue generation are material and are only expected to increase as LLM-based solutions improve. In the coming years, we expect to see more “AI Agents” or “Co-Pilots” augmenting or replacing every function, widening the delta between companies that adopt these technologies and those that do not.

Six enablers need to be in place to achieve the cost savings and value creation mentioned above: three technical (infrastructure) and three soft (business). We discuss these enablers in the following chapters.

3. Infrastructure enablers require further localization

Six main enablers are necessary to unlock the AI Agents opportunity in the GCC: three are technical enablers, and the other three are business enablers. The three technical enablers are models, data centers, and data assets - discussed below.

Models: local dialects, locally hosted and managed

Most AI Agents are built by “gluing” together a set of models to solve a specific business use case. Typically, companies use off-the-shelf components (open source) or third-party AI providers to complete their offering.

For example, an AI Agent company targeting the US market that needs text-to-speech capabilities would likely turn to third-party providers like ElevenLabs (recently raised $80M) or its smaller competitor, PlayHT.

In the GCC region, localized models are limited. For instance, there is no locally-hosted or open-source text-to-speech model with a Saudi accent. As a result, AI Agent companies in Saudi Arabia must build this component from scratch to meet local needs, a challenge that companies in other markets don’t face.

To close the gap in AI models, the GCC should focus on two key actions: (1) developing models tailored to local dialects, particularly speech-to-text and secondary LLMs, and (2) offering these models as locally-hosted managed services for companies to use (inference) or making them available as open-source. This could be achieved through incentive programs that encourage startups to specialize in these models, or through government-affiliated entities leading the development and servicing. Importantly, these models must be easily accessible to users worldwide, with a simple sign-up process and credit card payment, avoiding the need for enterprise-level sales teams.

Data Centers: boost GPU-enabled capacity

Generative AI relies on GPU-enabled data centers for both model training and inference. Large enterprises and regulated entities often require all computation to happen locally, either within their country or on-premise in their own data centers. While training in global data centers is typically acceptable (depending on the dataset), inference will always need to be done locally for regulated entities. In large countries like Saudi Arabia, this becomes a challenge due to the limited number of GPU-equipped data centers. Indeed, Saudi Arabia data center capacity per GDP is at 25% the one of North America.

Data Assets: unlock local, high-quality datasets

To build effective AI models, especially in the context of Generative AI, you need access to large volumes of data that reflect the local language nuances and cultural context. While these can be used in finetuning and regional benchmarks, GCC can also play a role in establishing world-class datasets in specific domains where there is an advantage, such as Energy or Healthcare.

4. Business enablers require funding, corporate engagement

The three main business enablers are capital, talents, and large corporations with the unique ability to enable B2B startups.

Capital: specialized and capable

Due to the early stage of the Generative AI sector and its rapidly changing dynamics, many conventional MENA VC investors hesitate to take on the risks or acquire the know-how necessary for the sector. As mentioned in previous sections, India (comparable GDP to MENA) invested $128m in H1 2024 alone, all focused on application-layer AI companies. Israel, a country with less than half of Saudi Arabia’s GDP, saw $93m invested in application-layer AI startups H1 2024, with the sector overtaking FinTech and Cybersecurity to become the most funded sector by number of deals.

Talents: enough to start, more is needed

Generative AI application-layer products rely more on traditional software engineering than specialized AI expertise. Therefore, the technological barrier to creating AI Agents isn't necessarily higher than in other digital sectors like SaaS. Often, the challenge is using existing components and tools to build platforms tailored to specific use cases. In this regard, the region's technical capabilities are sufficient to capitalize on this opportunity.

Having said that, the region’s strategy should always revolve around attracting and retaining the best global talent, whether AI-specialists or otherwise. While we do not believe that the local talent scene should slow down the GCC from creating value in the application-layer of Gen AI, we are still keen to see this advantage grow and compound to global scales.

Customers: the role of corporates is critical

The GCC needs more mega-corporations to engage with startups. Every B2B company starts with its first customer contract. When a large entity, such as a bank, retail group, or telecom, partners with a seed-stage startup for a proof of concept (PoC), it marks a critical milestone. This success attracts later-stage investors, creating a virtuous cycle of product development and new customer acquisition. This cycle is essential for B2B growth and market expansion. In developed markets like the US, Fortune 500 companies often have dedicated Startup Engagement Teams to foster collaborations and drive mutual value. An incentive program in the GCC (or a simple leaderboard PR) could have an outsized impact on the birth of B2B digital startups, which can later expand beyond their homebase region.

5. Time to action: a window of opportunity is closing

As local investors, we believe we are in a window of opportunity to establish a second homebase for AI giants, and with the right actions, the GCC region is uniquely positioned to seize it.

Consider India. Following the SaaS boom of the 2010s, it emerged as a major player, second only to the United States. Entrepreneurs and investors recognized the opportunity early, developed their product and growth capabilities, and today lead multiple niches with companies like Zoho ($1b+ revenue), Freshworks ($10b IPO), CleverTap, Shipsy, and BrowserStack being a few examples.

We now face a similar dynamic in the AI application layer. With countries worldwide starting from roughly equal footing, it is the perfect time to position our local market as a second homebase. What is needed is (1) capital, (2) talent, and (3) customers.

History shows that successful startups create ecosystems that fuel future ventures - think of the PayPal Mafia or the Careem Mafia. By acting now, we can foster the rise of AI application-layer giants in MENA, creating a lasting impact on the region's tech landscape.

MIND THE GAP: A $20bn GROWTH FUNDING GAP

INTRODUCTION

This report underscores a projected $20 billion funding gap in MENA in the coming period. In the past five years, the abundance of early-stage investors helped position MENA technology ventures on the exciting trajectory they have today. As these companies graduate to advanced levels, the scarcity of growth-stage capital poses a risk to the sustainability of this momentum. We believe MENA can benefit from more venture capital funds specializing in growth stage, and the role of government is crucial to continue development further up the technology investment value chain.

The MENA venture capital sector experienced a significant breakthrough in 2018 when a handful of institutional investors began actively supporting numerous technology companies. Over the past five years, this momentum has resulted in funding more than 2,000 startups, with over $9.0 billion in equity investments. Presently, there are ~220 companies that have successfully secured Series A or later funding rounds, which are referred to as 'growth-stage' in this report [1]. This marks a historic milestone as the Saudi Arabian and overall MENA VC ecosystem enters its growth-stage phase for the first time.

In terms of funding requirements, the growth-stage segment of ventures demands ten times more capital compared to its early-stage counterpart. However, despite this higher capital requirement, the risk profile of growth-stage ventures is significantly lower. This presents an excellent opportunity for investors to deploy substantial capital into companies with a lower risk profile that can deliver attractive returns within a relatively short time frame of 2-5 years.

So why is there a gap in the availability of growth-stage capital today in MENA? The average AUM of a growth-stage VC fund is much larger than that of an early stage fund, meaning that growth-stage fund managers need to raise from institutional investors such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), pension funds, endowment funds, and the likes, as opposed to early-stage funds that mainly target high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) or family offices. However, such institutional investors have rigid internal policies that prioritize capital allocation to funds showing a proven track record in terms of exits and realized returns. Such a track record does not exist yet for MENA growth-stage funds, simply because the industry is still too young and has yet to see the necessary number of materialized exits. A typical startups’ cycle from inception a fund-returning exit is typically 8 years, and most MENA success stories have not existed for that long today.

On one side, more capital is needed to fuel growth-stage companies and enable them to achieve successful exits, and on the other side, successful exits are needed to generate the positive track record that would allow VC investors to raise additional capital. How can we break such a detrimental circular dependency? The ignition of a new industry is one of the clear cases for government intervention. Bridging the growth-stage funding gap would represent the final step in the efforts of MENA governments to complete the activation of a thriving tech venture ecosystem. The emergence of a pioneering cohort of successful technology ventures will establish the track record necessary for private investors to confidently allocate capital, enabling the self-sustainability of the ecosystem.

1. MENA has successfully ignited its technology ecosystem

Inception is the most difficult phase of establishing a thriving innovation ecosystem. This is a time when there are no successful cases to serve as role models and inspire future founders; experienced talent is limited because of the lack of technology companies that make them thrive. Funding is discouraged by the absence of proven successes. Regulation is often unfavorable or simply ignoring of the needs of tech business models. The potential acceptance of technology from consumers and businesses is unknown. This long list of challenges needs to be addressed simultaneously.

The nature of the tech entrepreneurship ecosystem requires a number of enablers to be in place and develop in sync. Therefore, kicking off a new innovation ecosystem is a very complex job. You need to attract and inspire entrepreneurs, devote effort and funding in incubation and acceleration activities, set-up a regulatory framework and incentives to stimulate the start-up of new businesses, foster the formation of a community through events and public relations, and fund a number of local early-stage VCs.

Key drivers of innovation ecosystem - STV framework

Saudi Arabia, alongside a majority of other GCC countries, has successfully executed these steps under decisive leadership that launched a comprehensive series of initiatives to stimulate the ecosystem.

Between 2018 and 2022, these efforts resulted in more than 2,000 MENA ventures that have received $9.0bn+ in equity funding. Of those, 220 are in the growth-stage phase today, i.e. ones that have raised a Series A or above funding round and are presumably looking to raise a Series B or above round. In that same period, Series B and later rounds represented only 4% of the total funding rounds conducted, and accounted for 49% of total capital deployed [2]. As we will discuss later in this report, this is far below the share of growth-stage funding in developed ecosystems.

2. There is a strong pipeline of MENA growth-stage companies

As the MENA ecosystem is maturing, the number of growth-stage companies has increased exponentially. Today, 220 startups have raised Series A+ rounds, of which we see ~160 that are active in the market [5]. This trajectory will continue to go upward in the next few years as the increasing number of start-ups funded in the last 5 years graduate to the late-stage phase.

Number of active MENA ventures having raised Series A and above, 2017-20225

Tech companies have been able to raise larger and larger rounds of funding on the back of a solid growth of their fundamentals, in many cases having achieved more than $100M in topline. This is the case for six of the STV portfolio companies which grew their revenues from a few millions at the time STV invested in them to more than $100m in annual revenue each.

STV Portfolio Revenue Growth (6 largest companies with of $100m+ LTM/ARR)

The MENA growth-stage companies span across several sectors with the majority of them focused on eCommerce, FinTech and Logistics. These sectors have the largest TAMs in MENA and are the ones with the highest likelihood to accommodate large-sized winners.

MENA Companies that raised Series A and above, end of 2022, split by sector [6]

Another sign of the ecosystem maturing and entering the growth-stage is the increasing activity in tech exits. Tech acquisitions have been on the rise in recent years, with a total of 190 acquisitions between 2018 and 2022. To date, we’ve seen 4 MENA tech IPOs, with a number of additional MENA growth-stage companies having publicly announced their plan to prepare for an IPO, including several STV portfolio companies such as Tabby, Floward, Trukker, and Unifonic

Select headlines of MENA tech companies announcing IPO plans

3. MENA needs ~$25bn in growth-stage funding

Venture-backed companies need to raise 10-20 times more capital during their growth-stage phase compared to when they were early-stage [8]. This is a time when the business model is proven and the focus moves from experimentation to scaling. This need for additional and larger capital injections allows companies to hire experienced executives, expand geographically, grow working capital, establish M&A initiatives, and many more levers that scale these rocket ships to become long standing, sustainable, and profitable companies.

Average deal size by stage and country, USD millions [8]

While the capital needed in growth-stage phases is much higher, the risk profile is significantly lower compared to the early-stage startups. This represents a great opportunity for investors to deploy a large amount of capital on lower risk companies that can deliver attractive returns in a relatively short time frame, as the exit typically materializes in a shorter time frame of 2-5 years.

Furthermore, large rounds are becoming more frequent as companies move from Series A to later series. Indeed, the number of funding rounds larger than $30m has constantly grown in MENA, moving from 5 in 2020 to 22 in 2022, and this trend is only set to continue. The number of $100m+ especially has seen a large spike in the last couple of years, with the first one occurring in 2020, as the region sees more and more Series C+ funding rounds.

Now that MENA is entering the growth-stage season, the relevant question becomes: is the available growth-stage capital sufficient to fuel emerging winners and enable them to cover the last mile until the exit? Using three different methodical approaches, we estimate a need of ∼$25bn for growth-stage funding in MENA in the next 5 years. This capital is required to enable the achievement of MENA full potential in the production of successful tech companies.

Method 1: VC deployment projections based on GDP size and ratio

In countries where the VC industry is well developed, the yearly deployment of VC capital is between 0.2% and 1.0% of their GDP, and the share of growth-stage deployment can be as high as 90% in some countries. In contrast, the average VC deployment as a ratio of GDP for the three MENA countries with the highest VC activity is only 0.11% (about half of the equivalent in more developed LatAm ecosystems), and their average share of growth-stage capital is less than 50%.

VC deployment as a % of GDP by country, 2018-2022 [11]

VC deployment share by stage and country, 2018-2022 [12]

In the chart below, we project the VC capital deployment in MENA assuming that the VC deployment to GDP ratio will reach 0.33% in 2028 and that the split between early-stage and growth-stage will be 25% to 75%, equivalent to what we observe in developed markets. This shows that MENA needs about $39bn in VC deployment between 2023 and 2028, of which $26B in growth-stage capital.

VC deployment in MENA, actual values and projections (USD Billion) [13]

Method 2: deployment projections based on potential MENA Unicorns

Based on our previous STV Insights report - “From start-up to IPO” - MENA has the potential to produce an additional 40 unicorns by 2030. Based on global benchmarks, each unicorn on average requires ~$270m of total funding [14]. This translates to a required total of $10.8bn to produce an additional 40 unicorns besides. Moreover, we expect a 40% success rate for growth-stage companies raising much larger rounds. This translates to a total of $25bn in funding requirement.

Method 3: graduation of ventures across the funnel

In new VC ecosystems, initial investments favor early-stage ventures. As successful early-stage companies mature, growth-stage opportunities arise. In MENA, companies typically take 8 years from startup to exit. The rise of early-stage companies in 2018 sets the stage for a new era of growth-stage companies today, 5 years later. This trend will likely continue as post-2018 companies advance. The table below shows averages in VC ecosystems similar to and including MENA.

Startup fundraise statistics and trends [15]

The graduation rate measures the share of start-ups moving through the fundraising funnel from one stage to the next. A company can exit the funnel either because it defaults, becomes self-sustainable, or records a successful exit.

For every 100 companies that close pre-series A rounds, 37 progress to Series A, 12 advance to Series B, 5 reach Series C, and 2 reach Series D and beyond, resulting in a cumulative total of 157 funding rounds. Companies that navigate through each stage of this process typically achieve an average total funding amount of $271m. Ultimately, an estimated $2bn in funding is required to facilitate the growth journey of 100 pre-series A companies, 80% of which allocated to growth-stage rounds and 20% to early-stage.

Illustration of funding needed for startups to go through the full fundraising funnel

Considering that MENA over the last 5 years on average had 468 startups born and raised their first round of funding each year, we estimate that the yearly funding needed will be $9.5bn of which $7.6bn per year would be allocated for growth-stage companies. Below we report the funding projections, considering the 158 MENA growth- stage companies existing today and assuming that on average the region will continue to produce 468 new start-ups yearly.

Projected MENA funding needs, early-stage and growth-stage

4. There is a large gap in MENA growth-stage funding

If the growth-stage funding needed in the next 5 years is about $25bn, how much is the dry powder currently available in MENA? To answer this question, we looked at the different categories of investors and we estimated the dry powder of each of them.

MENA growth-stage VC investors and capabilities

1. MENA Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs)

MENA SWFs invest in growth-stage tech companies either through dedicated VC funds/ divisions (e.g. Sanabil under PIF, and Mubadala Ventures under Mubadala), or directly from the main fund (e.g. ADQ). Despite the investment activity of these players having been quite sporadic to date, they have sizable AUMs and the dry powder necessary to potentially become more active going forward. The estimated dry powder for this category of investors that we arrived at was based on their maximum growth-stage VC deployment in a single year.

2. MENA growth-stage VCs

Funds that focus on growth-stage have typically at least $300m of capital commitments that enable them to allocate up to $45m to a single portfolio company, giving them the ability to lead rounds larger than $100m and double down on their performing portfolio companies. In MENA, only two GPs have that capability: STV, who manages a $800m fund, and Impact46, who manage a number of growth-stage and single-asset funds. Both funds are focused on MENA technology companies and are sector agnostic. The estimated dry powder of these funds is based on their fund sizes, new commitments, and estimated capital deployed.

3. Global growth-stage VCs investing in MENA

These are VC growth-stage funds that either have a mandate focusing on other regions but from time to time invest opportunistically in MENA, such as Sequoia Capital India & SE (now Peak XY Partners) or are funds with a global mandate such as SoftBank, General Atlantic, Prosus and Tiger capital. Estimated dry powder for these investors is based on fund sizes, deployed capital, and ratio of MENA VC deployed capital to total deployed VC capital.

4. Other non-VC MENA investors

These investors are MENA based or they are active in MENA across a broad range of asset classes. Their attention to technology ventures could vary over time as the VC asset class is competing with others. Furthermore, while some of them possess capabilities that are relevant also to growth-stage tech ventures such as Gulf Capital, Invest Corp and Kingdom Holding, others are more generalist such as family offices or investment brokers. Estimated dry powder for these non-VC focused investors is based on AUMs and ratio of VC deployment in MENA.

Tech growth-stage MENA companies need investors with both, consistent focus and specialized capabilities. The consistent focus is necessary to ensure continuous availability of capital and to avoid the risk of such capital being diverted to competing asset classes from time to time. Specialized capabilities are needed to price, support value creation and steer emerging winners toward successful exits.

The only two categories of investors that have such attributes are the VC arms of regional SWFs and the regional growth-stage VCs. Thanks to its $800m fund, STV has been the most active with 27 growth-stage rounds lead between 2018 and 2022. The activism of the venture arms of regional SWFs have been largely sporadic so far but has recently shown more consistency. On the other hand, the non-MENA growth-stage VCs returned to focus on their core markets during the turbulent market conditions in 2022 after having conducted a few investments in 2021, further increasing the gap in available growth-stage capital. Other non-VC MENA investors played a significant part in temporarily bridging that gap , but it is still unclear how much focus they will continue to dedicate to the growth-stage tech segment.

In the chart below, we report our estimate of the $4.2bn dry powder currently available to MENA growth-stage companies. Compared to the $25bn funding need, this means that the market is experiencing a $20bn+ funding gap.

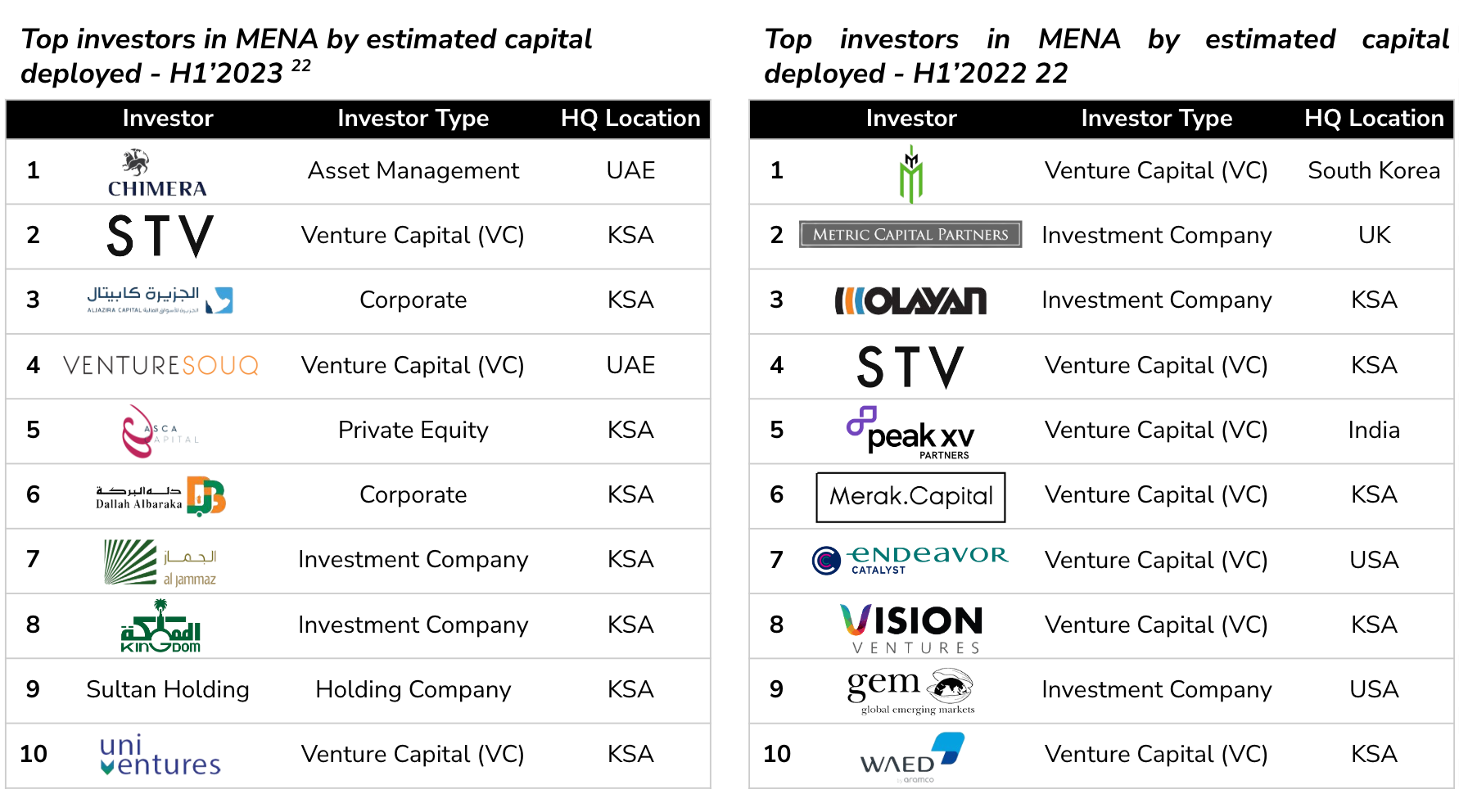

In 2023, the funding gap in the MENA region is already having clear effects that are prohibiting the region from reaching the full potential outlined in Chapter 3. Funding in the H1’2023 plummeted by 42% compared to the same time in 2022. Not only that, but the number of active investors also decreased by over half, a 55% decline to be precise.

MENA Funding by Half Year, 2019-2023 [18]

A major reason for this drop is that international investors, who were quite active in the region previously, have retreated from the region. These investors played a big role in 2022, making up 50% of investors in late-stage deals. But by the first half of 2023, their participation dropped to only 28%. [19]

An interesting shift is seen when we zero in on the top contributors. In H1 2022, the top 10 investors, ranked by their estimated deployed capital by Magnitt, were responsible for 26% of the total deployed capital. Fast forward to H1 2023, and this number skyrocketed to 62%. However, the composition of these top investors reveals more. In 2022, of these leading 10, only 4 were based in MENA and 7, i.e. majority, were VC funds. This year, in a telling turn, all top 10 investors are MENA-based. But, notably, only 3 of them are VCs, with STV being the only investor that retained its top 10 ranking in both years. [20]

Active Investors in MENA Startup Rounds [21]

Local investors, ideally positioned to bridge this funding gap, face a liquidity challenge. The available 'dry powder' or immediate funds are limited, constraining their ability to make substantial investments. It's a precarious balance: with international investors taking a step back and local investors facing constraints, the funding ecosystem staggers.

Worldwide, unicorns typically count 3 growth-stage investors among their shareholders. On average, VC funds manage 20 companies in their portfolios, with ~20% of these achieving the returns that align with the established power law VC fund pattern. Considering our earlier projection of generating 40 more unicorns in MENA, this underscores the requirement for at least 10 growth-stage VC funds in the market.

Average global unicorn-investor dynamics [23]

5. Government can play a critical role in bridging the gap

As previously mentioned, growth-stage VC funds need to raise capital from institutional investors such as SWFs, pension funds, endowment funds and the likes. However, such institutional investors have quite rigid internal policies that prioritize capital allocation to funds showing a proven track record in terms of exits. Such a track record is not available for MENA growth-stage funds, simply because the industry is still too young. So, on one side, more capital is needed to fuel growth-stage companies and enable them to score successful exits. On the other side, successful exits are needed to generate a positive track record that would allow VC investors to raise additional capital. Who can break such a detrimental circular reference? The ignition of a new industry is one of the clear cases for SWFs and Governments intervention who can play a pivotal role without distorting the market.

In a developed ecosystem, the private market will solve both issues, but in a nascent ecosystem such as MENA this will not happen. The main bottleneck is the lack of track record on exits that discourages private investors to deploy capital into growth-stage funds. The role of the public sector becomes critical. A number of initiatives can be considered to address this issue.

The public sector needs to inject more capital into MENA growth-stage funds. This responsibility can be assigned to different categories of capital allocators:

Public Funds of Funds

SVC and Jada played a critical role by allocating on average $10-30 million to early-stage MENA/ Saudi funds. Over time they have developed the capabilities to conduct rigorous due diligence on GPs to guide their development, and have gained a deep understanding of the ecosystem. They are well placed to fulfill a similar role with growth-stage funds by increasing their allocation to $100-300m per investment.

2. SWFs

SWFs could start directly allocating funding to growth-stage funds. The larger size of the allocation compared to the early-stage funds is more compatible with the SWF’s typical ticket size. Furthermore, a direct collaboration between SWFs and VC growth-stage investors could be mutually beneficial as the SWF could gain better access to successful tech ventures that could be further elevated with their support in the context of an IPO exit or global expansion.

3. Pension funds

Pension funds are among the most relevant investors in VC globally. In most of the GCC, pension funds do not have the mandate to invest in MENA VCs, and on the contrary in some cases they are prohibited from doing so. Today, MENA VCs represent an attractive asset class. Furthermore it would be sufficient to have a minimal allocation of the huge AUM managed the regional pension funds to move the needle for the VC industry and start building long-term sustainable relationship between regional pension funds and regional VCs

Public funding sources for growth-stage capital could be allocated to different types of players.

Existing regional growth-stage VCs

The existing regional growth-stage VC are the best positioned to keep steering the ecosystem forward. They have the track-record, the knowledge and the understanding to identify and support the tech ventures with the highest potential.

2. Regional early-stage funds

There is an opportunity to selectively uplift regional early-stage VCs to growth-stage VCs by providing them with additional funding to follow-up on their portfolio or helping them to raise a larger growth-stage fund. Early-stage VCs have gained relevant expertise and knowledge and providing them with the necessary funding to double down on their portfolio winners would help them through an organic transition to the growth-stage segment.

3. Global growth-stage VC funds

Global growth-stage VC funds can bring relevant expertise and potentially also FDI to the MENA ecosystem. Some of them have already sporadically invested. They could be further incentivized to establish a permanent office in the region and to deploy within the region the capital committed by Government funds.

Growth-stage investors and funding sources

6. Conclusion

In light of the evident potential and progress of the MENA tech ecosystem, which is well ignited and poised to produce several successful technology champions, the pressing $20bn funding shortfall cannot be overlooked. While the region's foundation is solid, this financial gap threatens to stall the momentum. It's time for local specialized investors, in tandem with government support, to champion this cause. By actively bridging the funding gap, we can ensure that MENA's promising trajectory isn't merely maintained but accelerated, cementing its place as a global tech powerhouse, and placing the region on the short list of the most attractive and innovative ecosystems.

FROM STARTUP TO IPO: UNLOCKING A $100B+ OPPORTUNITY IN MENA

INTRODUCTION

MENA is one of the most attractive markets for the development of technology ventures – it has now reached an upward tipping point in its growth trajectory. We believe the region can output 45 unicorns by 2030, and can create digital giants that can list on public markets, remain independent, and keep their focus on delivering innovative solutions tailored to local needs. In this paper, we share some of our analysis and learnings and we take the opportunity to contribute our viewpoint on how to further enable and nurture the ecosystem with the participation of all players. We also share a playbook on scaling technology companies across multiple sectors and countries in the MENA region.

A SPIKE IN TECH DEMAND AND CRITICAL GAPS IN OFFLINE OFFERINGS CREATE LEAPFROG OPPORTUNITIES IN MENA

More than 55% of MENA’s population is younger than 30 years old and it is growing at a 1.6% per year rate. MENA’s population are avid consumers of digital media, with an average daily social media consumption of 3.5 hours. These statistics set MENA apart in comparison to any other region across the world.

MENA’s young, fast-growing, and tech savvy population has high spending power and is keen to utilize technology for shopping, transacting, learning, and socializing. This translates to a strong demand for digital products and services across industries. Technology ventures that have the ability to cater to the tastes of this attractive user base can achieve accelerated growth and deliver strong unit economics.

On the supply side, traditional offline offerings show significant gaps across different sectors, providing technology ventures with easy access to underserved users and consumers. Those gaps are especially apparent in the banking sector, where more than 45% of MENA population is still unbanked; and in the retail sector, where the leasable retail area per capita is still one fourth that of developed markets. Such gaps boost the Fintech and eCommerce opportunity and consequently lead to prolific venture activity.

The list of underdeveloped sectors offering leapfrog opportunities is long and includes logistics, which is still underdeveloped and extremely fragmented, as well as real estate discovery، purchasing, and financing, currently underserved due to lack of market transparency and the dominance of informal and non-professionalized network of independent real estate brokers.

THE EVOLUTION OF MENA'S TECH ECOSYSTEM IS AT AN UPWARD TIPPING POINT WITH AMPLE HEADROOM FOR GROWTH

In 2019, we projected in our ‘How Much Can the Venture Capital Industry Grow in Saudi Arabia by 2025?’ report that it would have taken 6 years for MENA and Saudi Arabia’s VC deployment to reach $2.6B and $500M, respectively. In reality, that was achieved in 2 years.

The growth of the technology ecosystem follows a power law rather than linear progression. This trajectory is characterized by a sudden acceleration that marks an upward tipping point. MENA witnessed this tipping point in 2021, with a steep increase of VC deployed capital and of growth-stage deals (defined as funding rounds larger than $5M). The acceleration of the economic and technological ecosystem is driven by a growing talent pool, tech infrastructure, consumer adoption, as well as broad macroeconomic and regulatory reforms. As these components reached critical mass, the ecosystem enjoys an exponential growth.

However, the ratio of VC development to GDP in MENA is still much lower than that registered by other countries and regions, showing that VC yearly invested capital still has room to grow at least 5-10X before catching up with peer regions.

MENA IS JUST GETTING STARTED IN UNICORN PRODUCTION WITH THE POTENTIAL TO OUTPUT 45+ UNICORNS IN THE NEXT 7 YEARS, WORTH $100B+ IN EQUITY VALUE

We analyzed the number of unicorns[2] produced over time in markets with GDP and/or population comparable to MENA such as Brazil, Germany, UK, India, and South Korea. We also included USA in the peer group after resizing its number of unicorns based on the GDP2 delta with MENA. We learned that the unicorn production trajectory follows an exponential path rather than a linear one. This trajectory is quite comparable across the analyzed markets.

Assuming MENA will follow a similar trajectory, we estimate it will produce 45 unicorns by 2030, 10 years after Careem became the first MENA unicorn. This top-down estimate is validated by our direct observation of a number of tech companies that year after year are approaching the $1B valuation mark. We believe that the STV Fund I portfolio has the potential to deliver a number of unicorns in the next 3-5 years.

At the same time, based on benchmarks of comparable markets, we estimate that the total equity value of the 45 predicted unicorns could reach $100B+, as some of those technology companies will reach a valuation much higher than $1B. In particular we believe that within the next seven years MENA will see the emergence of decacorns, a technology company worth at least $10B in equity value.

THE OPPORTUNITY FOR TECH GIANTS TO EMERGE IS STILL OUTSTANDING

Most regions globally have seen the emergence of a technology giant, a multi-sector and multi-country player that secured a massive customer base and sustainable competitive advantage.

A NUMBER OF DRIVERS SUPPORT THE EMERGENCE OF A REGIONAL TECH GIANT

There are several drivers that make the emergence of a tech giant a natural evolution of any regional ecosystem. Tech giants have a business model that provides them with a number of unfair advantages that translates to a semi-monopolistic power.

Network Effects: Some tech platforms benefit greatly from network effects, where the more users are on-boarded, the more valuable the service becomes. This flywheel is especially utilized by cross-country and cross-industry tech giants in an interconnected region, where network effects of one offering benefit the remainder.

Customer Retention: Digital giants typically offer a subscription option that provides valuable benefits to its customers such as free delivery or reward programs. These marketing tools have been proven to significantly increase customer retention and ARPU (average revenue per user).

Cross Selling: Once a player has secured a large customer base through its initial offering, it becomes cost efficient for them to cross-sell additional products and services. In other words, these players enjoy a lower CAC (customer acquisition cost) compared to single-offer players. The cross-selling power become particularly strong in players that have high-frequent interactions with their customers (eg. ride hailing, food delivery, eGrocery). The daily or weekly touchpoints with the customers favor a higher level of trust and awareness, and more frequent opportunities to cross sell a wide offering.

Customization: The collection of a larger data set, enables digital giants to extract superior insights to continuously fine tune its offering, pricing, and delivery to each customer.

Economy of Scale: Like in any other business, large scale unlocks not just cost efficiency but the opportunity to attract superior talents and increase R&D investments.

TWO EDGES MAKE SAUDI ARABIA THE NATURAL HOMEBASE FOR MENA DECACORNS: HIGH GDP & DEEP PUBLIC MARKET

With respect to scaling technology companies, Saudi Arabia is undoubtedly the gravitational center of the broader MENA catchment area, which also includes Central Africa, Southeast Europe, and Southwest Asia.

Saudi Arabia’s power of attraction is determined by two main drivers:

GDP size, which accounts for around one third of MENA’s total GDP. Cracking the Saudi Arabian market is necessary for most MENA startups that want to achieve unicorn status, irrespective of their initial country of origin.

Stock exchange size and depth, which is increasingly considered by VC investors as the preferred exit gate. Furthermore, the opportunity to exit through IPO positively impacts the strategy and the level of ambition of MENA tech ventures that are moving from developing a specialized and conventional offering to become attractive acquisition targets for global players, to developing solutions tailored more to the regional market with the vision to become self-sustainable regional leaders.

SAUDI ARABIA STOCK EXCHANGE DISPLAYS STRONG FUNDAMENTALS AND POSITIVE TRENDS

Saudi Arabia is going through a transformational phase, driven by the introduction of a multitude of programs and initiatives, the adoption of progressive regulations, and the support to nurture a vibrant private sector and growing talent pools. The KSA public market has recently seen positive reform that aligns with global best practices, leading to the inclusion of the Saudi public market in the MSCI and FTSE indices since 2019, as well as the first successful IPO of a VC-backed Saudi tech venture. This single IPO saw an oversubscription of 20X, showing a strong investor appetite for tech companies.

The role of regulators and government stakeholders has been pivotal in igniting this journey and attracting regional and international resources toward a clear and compelling vision, including:

The Financial Sector Development Program (FSDP), key in realizing Vision 2030, achieved major reforms in KSA public markets, evidenced by the inclusion of the Saudi market in international indices and the launch of derivative products. The program also resulted in the licensing of 3 digital banks, the launch of FinTech sandboxes under SAMA and CMA, the push for a cashless society, the launch of FinTech Strategy Implementation Plan, and the outlining of an open banking framework.

The New Saudi Companies Law, which tackles major legal obstacles for startups and VC investors through a flexible form of companies called “Simple Company” that allows for certain economic terms, minority control, and other customary VC terms not accepted under other company forms.

The opportunity provided by FinTech sandboxes that aim to test solutions before granting providers full licenses was critical to ignite this high-potential sector. The Open Banking policy outlined by SAMA in late 2021, which will require banks to adopt API policies, is a great first step towards digitization that will facilitate the emergence of innovative FinTech solutions as the ecosystem matures.

VC deployment in late-stage ventures creates market cap potential as a result of the high-growth and minority-interest style, multiplying the equity value of the initial investment. Our analysis indicates that the acceleration of late-stage investments creates a $100B+ market cap opportunity that can be captured in Tadawul by 2025. We are seeing early signs of realization, as Jahez IPO for example captured half of the the market cap potential in 2022.

As mentioned earlier, MENA presents a favorable context for the development of large technology companies. Today, the Information Technology sector’s share of the S&P500 is 48x larger than its counterpart on Tadawul. In only 5 years, technology companies took over the top ranking of US stock market. There is no reason why the technology sector on Tadawul cannot become as relevant as it is today in more developed markets.

To provide competitive IPO offerings and to enable an efficient and fast process for corporate action, corporate and tax requirements and policies need to align with the most competitive global markets. This will in turn reduce IPO waiting times and facilitate startup funding in a timely manner, as well as ensure that VC divestments meet fund lifetimes. These requirements include allowing governance and control for minority investors and minimizing dilution for founders, reducing the tax impact associated with corporate restructuring, minimizing capital gain tax in line with the most attractive jurisdictions, and standardizing treatment of resident and non-resident investors.

STV HAS IDENTIFIED A STRATEGY ON HOW TO DEPLOY CAPITAL AT SCALE TO CREATE AND ANCHOR DECACORNS IN SAUDI ARABIA

Working and strategizing side by side with our portfolio companies enabled us to identify a playbook for MENA ventures to scale up and to address two major challenges: the fragmentation of our region across a number of countries, and the often limited size of total addressable markets.

This playbook consists of three main phases: the first phase aims to grow the venture into a successful and sizable platform by cracking the Saudi market. The second phase focuses on cross-border expansion, and aims to inorganically boost the growth rate of the venture through M&A by leveraging the capabilities and know-how developed in phase 1. M&A represent an efficient tool to enter new geographies and product categories, and to overcome market size limitations of the initial focus. This is particularly applicable for markets with high barriers to entry and for companies whose products are challenging to organically scale across borders. Finally, phase 3 aims to maintain company independence – compared to being acquired by foreign entities – and to maximize growth potential through IPO.

There are a number of companies in our portfolio that are already in advanced stages of this playbook, and may soon have the opportunity to list publicly. We foresee several others that have the potential to follow a similar path as well.

MENA is on an unprecedented and accelerated path to unlock a $100B+ opportunity for tech ventures. This is driven by top-down reforms and initiatives, and is fueled by a young and tech savvy population, an integrated regional ecosystem, and a deep public market in KSA. We believe that the way to achieve this potential is through cracking the largest market in the region, replicating that success through in-organic growth channels, and finally maintaining regional independence while maximizing growth.

[1] Numbers for US, Canada, Singapore, Australia, KSA, and Oman are from multiple cities.

[2] Technology Companies that have reached an enterprise value higher than $1B

[3] US GDP ($22.7T) is 8.7X the GDP of MENA. In order to make USA comparable to MENA, in this chart we have scaled down the number of USA unicorns by a factor of 8.7.

[4] STV estimate based on comparative analysis of unicorn valuations in similar regions (Latin America, Europe, APAC)

[5] Listed market cap are as of market close on 31st of December of the listed year

How Much Can the Venture Capital Industry Grow in Saudi Arabia by 2025?

Executive Summary

Venture capital (VC) investments in Saudi Arabia are growing rapidly, and yearly invested capital has the potential to expand tenfold to $500 million in 2025 from $50 million in 2018. The realization of such a growth trajectory will result in a cumulative injection of $2 billion between 2019 and 2025. Of that total, STV estimates that $350 million will target early-stage ventures, with the rest deployed across the ecosystem, from Series A to late-stage ventures.

An aggregate annual VC ticket size of $500 million would align Saudi Arabia to countries where the VC industry has played a significant role in the economy – countries such as France, South Korea and UAE where VC’s annual investment is equal to 0.1% of the GDP. Reaching $500 million by 2025 implies an average yearly growth rate of 40% over the next 7-years – a trajectory other countries have achieved, and an ambition Saudi Arabia appears capable of achieving.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia’s status as the region’s economic powerhouse indicates a clear opportunity for the Kingdom to capture its fair share of MENA VC investments compared to GDP. This would have been the equivalent of $235 million in 2018, assuming it secured 35% of MENA-invested capital, in line with its share of regional GDP.

We believe Saudi Arabia is now on the cusp of realizing this potential for the following reasons:

Strong demand for tech products from consumers, businesses and the government

Recent exits have validated the VC model in the region, while successful Saudi-born tech solutions have enhanced the technology sector’s appeal to talent

The tech ecosystem and value chain are developing rapidly as enablers that accelerate the formation of digital ventures are established

A growing presence of incubators and VCs has positively contributed to the maturity of the ecosystem

Ease of doing business has improved significantly in line with new entrepreneur-friendly regulations

A number of critical changes are required to support the ecosystem’s growth. Among these are amendments to the Saudi Companies Law and legislation to allow the enforcement of the kind of debt instruments that VCs are more familiar with in more mature markets. Rolling these out will go a long way towards channeling investments for seed and early-stage startups. The availability of talent also remains a primary bottleneck, but Saudi youth are motivated and inclined towards tech and enterprise, and coupled with access to the virtual education resources, we expect this gap to narrow in the near future.

Despite these challenges, the Saudi Arabian start-up scene presents attractive investment opportunities for VC funds, thanks to new government regulations, a maturing value chain, and most of all, a fast-expanding market for tech.

Venture capital investments in Saudi Arabia are growing rapidly…

VC activity in Saudi Arabia is booming following a recent surge in activity. VC investments grew to $50 million in 2018 from $7 million in 2015, publicly available data shows. That is a 90% jump in CAGR over the last three years, deployed across approximately 90 ventures. The figure likely reflects only a portion of actual investments, as many seed and early capital injections remain unreported. [1]

…and there’s room to grow tenfold, benchmarks indicate

STV analyzed the ratio of VC investments in Saudi Arabia to national GDP to determine the industry’s potential economic impact in the country. At 0.01% of GDP in 2018, the industry has substantial room for growth within the Kingdom.

By contrast, for countries such as Brazil, France, and the UAE—where VC plays a significant role in the economy—the ratio averaged 0.1%. In countries where VC is a leading economic force, the ratio stood at 0.4%. And, in countries where VC plays a transformative role, such as Singapore and China, the ratio was 1.4% and 0.78% respectively.[2]

Realizing Saudi Arabia’s potential in accordance with the average ~0.1% ratio means that VC investments in Saudi must grow tenfold to reach $500 million per year.

Saudi VC investments can reach $500 million by 2025

The forecast of $500M yearly investment by 2025 is supported by recent growth trend recorded by Saudi VC investment and by the growth rate recorded by benchmark countries.

VC investments have been expanding by 90% annually between 2015 and 2018. This upward trend continued in the first half of 2019, with a growth rate of 82%[3] compared to the previous semester. We should expect growth to slow down as the absolute amount of invested capital increases. An assumed CAGR of 40% between 2018 and 2025 implies a drop in the yearly growth rate from 90% in 2018 to 15% by 2025. The realization of such a growth trajectory will result in a cumulative investment of $2 billion over the forecast period.

We believe that this forecast provides a reasonable projection, considering the many positive policy changes and incentives driving Saudi Arabia’s VC market today. Furthermore, the VC industry has already demonstrated its ability to sustain high growth rates over a prolonged time frame in other economies, both emerging and more mature. Our findings confirm that the 40% yearly growth expected for Saudi Arabia can be surpassed. The following chart demonstrates that those trends are not uncommon, especially in fast-growing markets.

Saudi Arabian VC could have been 6x larger

Saudi Arabia has a clear opportunity to boost VC activity. In 2018, only 9% of regional VC funds were deployed in the Kingdom, although the economy accounted for 35% of the MENA total. If VC investments in the Kingdom were in line with its relative GDP weight, they would have accounted for $235 million, or more than 6x 2018’s $50 million investment.

Almost 70% of MENA VC investments were deployed in the UAE over the study period. That’s perhaps understandable as the UAE has consistently facilitated access to talent. It has also fostered an active ecosystem through favorable regulations and a startup-friendly environment that incentivizes entrepreneurs to choose the country as their launchpad.

However, owing to its economic heft, its people’s purchasing power, and the changing entrepreneurial landscape, Saudi Arabia is emerging as the largest market for ventures in the MENA region, and is the market that can allow companies to scale exponentially. As the Kingdom continues to realize the economic benefits of its Vision 2030 reforms, we expect to see more businesses gravitate towards Saudi Arabia, as we have seen with Amazon.com and the San Francisco startup Cambly, an English-language learning community. Such activity will no doubt further support Saudi Arabia’s VC growth.

Capital allocation will swing towards later-stage investments

As the VC industry develops, a higher number of ventures will qualify for follow-on investments. Consequently, the sector will naturally rebalance towards later-stage investments, further aligning with mature markets.

We estimate that the share of investments in early-stage versus later-stage ventures will decrease from the 25% recorded in 2018 to 15% in 2025. This trajectory will result in $350 million invested in early-stage ventures as compared to $1.6 billion in later-stage activity over the years from 2019 to 2025.

The maturing ecosystem creates favorable conditions for our forecast

Saudi VC investment growth recorded over the last three years has been propelled by many forces. Established industries such as agriculture, transportation, logistics, and healthcare are being transformed by local and regional startups. Many other sectors are ripe for disruption.

We see significant and positive development across the six main dimensions that determine the VC industry’s ability to flourish. Those dimensions, or growth pillars, summarize why we are confident that the future of Saudi Arabia’s VC and tech ecosystem will only get better.

1. Strong tech demand from consumers, businesses, and government

Demand for smart tech solutions to meet lifestyle choices among Saudi consumers has been a major driving force for the development of new products and services. The fact that Saudis are connected and extremely tech-savvy is not surprising. It is not uncommon to see Saudi Arabia topping the charts for smartphone penetration, YouTube views, or Snapchat consumption. Saudis, today, are also active contributors to the digital economy, led by the growth of the wider ecosystem.

Signals of this behavioral shift are plenty, and the evolution of Saudi consumers’ role in the digital economy has been impressive. The E-Commerce in MENA report developed by Bain & Company [4] indicates that the average basket size for online purchases today in Saudi Arabia is around $150—akin to mature markets such as the US and UK and greater than the average Chinese basket of $100. Amazon’s acquisition of Souq.com and its recent hiring push confirms the opportunity that the e-commerce giant sees in the country.

Saudis are also now earning through online channels, whether through eSports or on platforms such as YouTube. The gig economy is providing new revenue streams to the Saudi population. Examples include apps such as ride-sharing platforms Uber and Careem, and delivery platform Mrsool.

Across the Kingdom, business and government entities are embracing startups as well. This is seen as more established institutions and governments begin to work with technology-first startups and integrate them into their business operations. Startups such as Unifonic, the cloud communications platform, and Lucidya, the Arabic-focused social media analytics tool, are partnering with Saudi Arabia’s most well-established institutions and government entities. As a result, trust in these and other emerging players is further solidified.

2. Success stories are feeding tech optimism among talent and investors

Startups like Noon Academy have shown how homegrown enterprises can expand from Saudi Arabia into the rest of the region, and not only vice versa. Unifonic, for example, has a demonstrated legacy of making cloud communications more accessible, and its services are used by international companies such as Aramex and Uber, and regional organizations such as Bank Albilad and the Saudi German Hospital.

Success is also being seen in other ways. Exits such as Souq.com (acquired by Amazon for $580 million), Careem (acquired by Uber for $3.1 billion), Carriage (acquired by Delivery Hero for $100 million), and Talabat (acquired by Rocket Internet for $170 million) have validated venture capital as a viable investment vehicle in the region.

As A16z's Marc Andreessen puts it, software is finally eating the world—a state of affairs that is now being replicated in the Kingdom. As the momentum continues to grow, we foresee a healthier pipeline of early-stage startups that can translate to later-stage investable companies, further raising prospects for Saudi VC investments in the medium- and long-term future.

3. Technological infrastructure are enabling even more start-ups

The advent of new infrastructural platforms has enabled a new class of entrepreneurs. Thanks to simplified retail solutions such as the digital storefront site Salla and logistics fulfillment company Salasa, anyone can now launch an e-commerce business within a matter of days. Salla, for example, already has 8,000 digital shops. In line with disruptive digital trends worldwide such as Shopify, this is only the beginning of Saudis’ engagement with the digital economy.

Payment solutions remain an important link in this value chain. From STC Pay to Paytabs and Hyperpay, we see a lot of developments in the space. However, we are eager to see a regional leader that can further unlock the digital economy in Saudi Arabia, the GCC and the wider MENA region.

4. The healthy presence of VCs and incubators is growing fast

In recent years, an increasing number of investors have been looking at Saudi Arabia’s youth-led demographics to create value. Consequently, more VC capital has made its way into the Kingdom.

The Saudi Venture Capital Company (SVCC) is among those companies that are actively enabling the ecosystem. It does so through direct co-investments with angel investors, venture capitalists, and sophisticated investors, and by investing in VC funds to catalyze venture capital investments and entry barriers for fund managers looking to operate in the VC market. STV is seeing more initiatives and policies that are further driving this growth.

5. Favorable regulation has significantly improved ease of doing business

The Saudi government has made great strides to unlock the nation’s digital and entrepreneurship ecosystem's potential. Recent policies such as the permanent residency program and expat ownership licenses will encourage entrepreneurs to choose the Kingdom as a startup base. Foreign founders can now apply for residency permits along with their families, own real estate, and have 100% corporate ownership in sectors such as education and healthcare. Most, if not all, of the tech ventures established in the region target the Saudi market. Many have already begun scaling up their operations in the Kingdom. Allowing those ventures to set up and fully run their businesses from Saudi Arabia will be a real turning point for the ecosystem.

The Kingdom’s new bankruptcy and commercial pledge laws fill important gaps in the legal infrastructure. SAGIA’s new Venture by Invest Saudiwill attract greater numbers of venture capital firms to the Kingdom, enabling entrepreneurial activity to flourish. This is a significant step forward for the ecosystem and a critical channel that will funnel valuable know-how and experiences from global VCs to local entrepreneurs. SAGIA also introduced the Entrepreneur License last year, to allow foreign founders to launch and expand start-ups in the Kingdom via co-working spaces and accelerators.

Fintech Saudi is accelerating the development of the financial services sector with its sandbox initiative, sharing frameworks and regulations, as well as providing options for international players keen on reaching the Saudi consumer. This can unlock potential not only within fintech, but also for many other sectors that rely on payments and financial solutions.

We also see greater potential across the GCC. Regulatory changes that can enable seamless cross-border transactions and operations will deepen existing synergies and allow local players to go regional — further tapping into resources and value pools across the GCC.

But there’s room to improve even further.

The time needed to complete a financing round can be cut significantly if Saudi Arabia is able to implement its own financial free zone, along the lines of the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) or the Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC). Such a move would mean that Saudi Arabia would not lose business to other jurisdictions. We also see room for improvements in capital requirements. Startups today are hindered by high minimum share capital requirements.

There’s also significant room to strengthen the legal infrastructure. Convertible notes and simple agreements for future equity (SAFEs) are unenforceable in Saudi Arabia. These instruments are the basis of most seed and early-stage financing and are very important to the health of new ventures. Employees' Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) do not exist under Saudi law. ESOPs are a virtue of start-ups around the world and are an essential way for tech companies to attract new talent. Finally, Saudi Arabia would also benefit from developing Preferred Shareholder Rights (PSRs). The vast majority of VC financing includes a standard suite of PSRs, including liquidation preferences and anti-dilution rights, which do not exist in respect of a Saudi entity.

The Saudi Companies Law requires amendments in order to ensure that these standard VC structures are available and enforceable in the Kingdom.

6. There’s a shortage of talent—but that could soon be fixed

The continued growth of the start-up ecosystem depends on sustained entrepreneurial activity. Beyond measures to build startup interest, finding and creating a talent pipeline remains the main enabler of a truly vibrant and fast-growing ecosystem. Demand for talent is not unique to Saudi, however, the gap between the supply of talent and demand from both local and global tech companies is widening fast.

But there's a light at the end of the tunnel.

As skills become obsolete ever more quickly, the tech industry has begun to increasingly rely on talent with an entrepreneurial spirit rather than counting entirely on seasoned professionals. A study published by Deloitte finds that the Saudi Youth have a much stronger motivation towards tech entrepreneurship compared to their international peers. STV research is proving that to be true on the ground as well. We have met with hundreds of Saudi founders who showed both the will and commitment to solve some of the most pressing problems facing the Kingdom and the wider region by leveraging the power of technology. These success stories, coupled with mentorship and youth engagement programs, can provide the inspiration and motivation needed for Saudi youth to take the leap into the startup world.

The tech industry also relies on a consistent supply of highly skilled engineers, product managers, business developers, and sales professionals. The internet offers innumerable ways for anyone with a device and a connection to acquire hard and soft skills. Whether these programs are self-taught or tracked, free or paid, locally produced or globally, they can help virtually anyone to build a relevant skillset for building digital ventures in as little as six months.